An exhibition by Pierre Leichner

November 2010

ŌĆ£Over the past five years I have been transitioning from a thirty-year career as an academic/ administrator psychiatrist to that of an artist. This desire is fueled both by a lifelong dream and by my dismay with the direction our health care system has been taking. During the past few years, I have become aware of many of the similarities between Science and Art. At their core, they share the pursuit of meaning… Both can embrace the same multi-factorial approaches to understanding, which includes biological, psychological, social-cultural, and spiritual factors. Furthermore, the past couple of years have seen an increase in my understanding that Art is not only about creating aesthetic emotion in an audience, but also about socio-political and philosophical issues.ŌĆØ (Leichner, Artist Statement 2007).

It is fitting that the setting of the ŌĆ£DSM ReŌĆōRevisedŌĆØ show is an emptied ward in what was once one of the largest psychiatric institutions in Canada–both because of the context of the issues explored by the works but also for personal reasons. It is because of my concerns about the commercialization of health care and its increasingly repressive administrative environment that I decided to turn to the arts to provide me with an outsider view and voice. The first carved DSM IV was done at the 3-bisf Center of Arts at the Psychiatric Hospital Montperrin in Aix en Provence. It is a centre where the public, patients, and artists take workshops and attend art events together without being categorized. The positive reaction to this work encouraged me to pursue this research further, leading me to discover book art and more about the DSM.

ŌĆ£Here is the book as sculpture, the book as bed, the book for burning, the book transformed, burnt, chained.ŌĆØ (Shapiro)

There is still debate on defining book art. Accordingly, there are many names for these works such as artistŌĆÖs books, bookworks, livres de peintre, and altered books. This is not surprising since art made with books has taken many forms reflecting the influences of the literary and art world of their times. But simply, one might consider book art as books made or altered by an artist who is self conscious about book form.

Perhaps, a more practical way to group these works is the one Betty Bright suggests in her book on Book Art in America (Bright). She names four categories:

ŌĆ£the letterpress-printed fine press book, where text is ascendant, the deluxe book, often dominated by imagery, printed through a print making medium and costly binding materials and the bookwork which can be subdivided into two distinct types (multiple and sculptural), whose contents interacts with or comments upon the book as an object or a symbol of culture. In the multiple, alteration usually occurs on the page with a new interplay between text and image. It is printed in large edition often cheaply and directed to reach a larger audience. A sculptural bookwork, in contrast, is a work perceived as sculpture that responds to, comments on, or undermines the cultural associations with ŌĆ£bookŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ (Bright, 258)

Historically, Johanna Drucker cites the French poet Stephane Mallarm├® as most influential with his work Un coup de des jamais nŌĆÖabolira le hazard in 1897. In it the text of his poems are freed of the usual columns and margins whose form contributes to its expressive power. Mallarm├® was attempting a synthesis of his concept of the book as a transcendental instrument and its physical form to embody new thoughts visually (Drucker). Drawing on the metaphors of Mallarm├®, Roland Barthes derived ŌĆ£the idea of the text as a continually changing construction formed through the process of readingŌĆØ (Drucker, 40). Jacques Derrida goes further in calling to question the finality of writing and sees the book as ŌĆ£never static and complete, always becomingŌĆØ (Drucker, 41).┬Ā Rucker eloquently summarizes the concept of the book as a metaphor, ŌĆ£an object of associations and history, cultural meanings and production values, spiritual possibilities and poetic spacesŌĆØ (Drucker, 42).

From the early 20th century books became a major form for artistic experimentation. This introduced interdisciplinarity in the practices of many of those involved. Poets, painters, and theater artists often collaborated. But, spurred on by conceptual practices, it was after mid-century that books became a self-sustaining realm of activity. Many renowned artists have since contributed to book art at some point in their careers. As one might expect, all major art movements have been reflected in these works. However one of the first to work with a book as an object was Marcel Duchamp with his ŌĆ£Unhappy ReadymadeŌĆØ in 1919. Duchamp asked his sister to hang a geometry textbook outside their Paris balcony until it was destroyed by the weather. This work is particularly relevant to my work because it can be described as one of the first altered books or as installation bookwork or even an environmental bookwork (Bright, 410).

It is somewhat paradoxical that I use a category to explore my work since it is in part a critique on the limits of categorization; however, a review of the altered books or the sculptural book form category is of particular relevance. It is only since the 1980s that these works have attracted attention. I like the term used by Riese Hubert: deviant books or livre detourn├® (Hubert). He describes these works in oppositional terms as creating a clash between the book as object and its intellectual, aesthetic and cultural dimension. When confronted with them, they evoke a mix of fascination and repulsion. They pit art against functionalism and reading against looking. They collide with our expectations of books, be they of intimate, protected memories or containers of secure knowledge and truths.┬Ā ŌĆ£Book 4 (DanteŌĆÖs Inferno)ŌĆØ by Lucas Samaras┬Ā (1962) or Barton Benes ŌĆ£Censored BookŌĆØ (1977) wreak sadistic havoc on the books by piercing them, binding them, covering them with needles rendering them untouchable and unreadable. John Latham possibly went even further by burning or chewing books in his installation/ performance ŌĆ£bookworks.ŌĆØ In 1964, in a performance called SKOOB Towers (books reversed) Latham set encyclopedias on fire near the British Library. He objected to their rigid mode of knowledge.

To Latham, books were not a path to knowledge but the residue of a closed and contrived system that upheld a network of political and economic interests (Bright, 130). In ŌĆ£Still and ChewŌĆØ he borrowed a copy of Art and Culture by Clement Greenberg, then he and friends chewed pages of the book and dropped the remains in sulfuric acid. He eventually sold the bottle of remains to the Museum of Modern Art in New York having thus appropriated and resituated artŌĆÖs discourse.┬Ā Drucker would describe these artistŌĆÖs books as agents for social change as they were produced with a political agenda to advocate for a change of consciousness on some area of contemporary life. (Drucker, 287)

Others found more pleasant or even erotic associations to which to subject their materials. Betsy Davids and Jim Petrillo Softness on the Other Side of the Hole (1976) plywood cover page has a hole in it that reveals hair behind it.┬Ā In the 1980s and 1990s artists started to address the change in our culture going digital. In How to Make an Antique, ŌĆ£How to Make an Antique,ŌĆØ Karen Wirth and Robert Lawrence (1989) force viewers to compare information delivery between video and books in a playful installation. This work perhaps points to the evolution of the altered bookwork when it joins with installation, video and performance art.

As the future of books is uncertain and digital options are increasing, books have become denaturalized as holders of knowledge or memories, spurring renewing interest and openness to using them as material for art. By altering books today one also cannot escape the questions about their future as the containers of our ever-changing knowledge and stories. As the paper book libraries empty out replaced with digitalized versions, more and more books are finding their way to dumps, and landfills, becoming part of the landscape and returning to the earth. A 2009 exhibition of altered books ŌĆ£Book BorrowersŌĆØ at the Bellevue Arts Museum included works by Brian Dettmer, Chen Long-Bin, and Guy Laram├®e. They make us aware of the book as an instrument for disseminating text and images promoting specific cultural, economic, political, and philosophical agendas. Through their dissemination they can shape the thinking of readers separated in time and place. However, it is worth noting that Drucker poses a narrower definition for the category of artistsŌĆÖ book and would question whether these works belong to it because these are sculptural pieces ŌĆ£which reference the book as a cultural icon rather than explore the potential and identity of book form.ŌĆØ (Drucker, 362).

Brian Dettmer deconstructs illustrated reference books by carving into them with scalpel bringing out their object-ness while masterfully picking out details, maps, illustrations, snippets of text, a kind of spatial hypertext, reinstituting their magic (Landow). Chen Long-Bin is a Taiwanese sculptor who uses waste materials such as telephone books to create sculptures that unify form and content. His “Guan Ying with Flower Crown (Ming Dynasty)” looks, from a distance, like a bust of the Buddhist Goddess of Compassion carved from mottled marble, but┬Ā┬Ā sheŌĆÖs actually made from Manhattan telephone directories.

Also relevant to my works is, Guy Laram├®e, an interdisciplinary Quebec artist for more than 25 years. Guy Laram├®eŌĆÖs work embraces a large disciplinary territory:┬Ā music, theatre, dance, video, painting, writing, sculpture and installation. Laram├®e sculpts landscapes with books. He sandblasts books into rocks, mountains, volcanoes, and plateaus. In ŌĆ£La Grande Biblioth├©que,ŌĆØ a whole Grand Canyon has been constructed from sandblasted volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Laram├®e’s “P├®tra” is a replica of the renowned Jordanian archaeological site, while ŌĆ£Toute les id├®es se ressemblent” takes slanted dictionary tomes as fodder for a craggy mountain landscape (Upchurch).┬Ā It is also of particular relevance as Laram├®e who also has a degree in anthropology has a specific interest in interdisciplinary practices and concerns about the divisions brought about by specialization.

During the Interdisciplinary Practices on Art Colloquium held in Montreal in 2000,

Guy Laram├®e remarked that artists are not shielded from the desire to function in the framework of distinct categories, that is, categories where inter-subjectivity is minimal. Furthermore, he states that artists are particularly sensitive to the struggle between rational thinking and language, and intuition and experiential knowledge. Unclear boundaries are uncomfortable. He goes on to say that we need myths to live and that, as we abandoned humanists, modernists and spiritual myths during post-modern times, we have replaced them with the scientific myth. Inert and biological material is all that matters and financial institutions direct this paradigm.

Art may have lost its place as furthering knowledge and human meaning to reason, business and scientists. The challenge for artists who seek to reclaim their myths resides in reaffirming the positive aspects of non-discursive cognition. We need to make art to understand, not only for pleasure or distraction and to redefine knowledge as a state of being. According to modern pedagogy, you have to be taught to know ŌĆśhow to do it.ŌĆÖ and it is only after you are trained that you are allowed to ŌĆśdo it.ŌĆÖ This connection between training and doing puts the holders of the knowledge in power and control of their territory. Once you share the knowledge you can claim the territory too. This is how selective disciplines lay claim to knowledge and create systems to protect their territories.

Laram├®e encourages us to ignore disciplinary boundaries and for artists to do what no one else can do. (Laram├®e). Making works in this territory without boundaries is perilous because one has to find their balance between: ŌĆ£Trop de Rigueur et pas assez de Coeur ou Trop de Coeur et pas assez de Rigueur.ŌĆØ┬Ā And if one had to summarize the flaws of the DSM it is that it has:

ŌĆ£Trop de Rigueur et pas assez de Coeur.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£One of the raps against psychiatry (DSMs) is that you and I are the only two people in the U.S. without a psychiatric diagnosisŌĆØ — David Kupfer

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM IV TR) is a categorical and rigid classification system that was created by researchers in the United States. North American clinicians, due in part to their need to legitimize psychiatry as a medical science, adopted it. Today this system is being globalized. This bridge that was established between clinicians and researchers has become more of a one-way street and has been seized by corporate administrators. Clinicians behave more and more like researchers and employees while patients are more often seen as economic commodities.

The American Psychiatric Association publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). It provides a common language and standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders. It is used in North America and increasingly around the world, by clinicians, researchers, health insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and policy makers. It has thus become a sort of Bible for psychiatry. The DSM, including DSM-IV, is also a registered trademark belonging to the American Psychiatric Association (APA). It is a bestselling publication from which APA makes huge profits and gains considerable clout in world psychiatry, especially as many reputed research journals require studies to use DSM classifications in order to be published.

The manual evolved from systems for collecting census and psychiatric hospital statistics, and from a manual developed by the U.S. Army.

DSM-I (1952) was 130 pages and listed 106 mental disorders.

DSM-II (1968), listed 182 disorders, and was 134 pages.

The DSM-III (1980) was 494 pages and listed 265 diagnostic categories.

DSM-III-R (1987) was 567 pages and contained 292 diagnoses

The DSM-IV (1994) was 886 pages and listed 297 disorders.

The upcoming DSM-V is currently in preparation, due for publication in May 2013.

The DSM has attracted criticism as well as praise.┬Ā Its global availability has worked towards decreasing stigma by legitimizing mental disorders and it has allowed for better identification and earlier interventions. It facilitates data collection. One of its advantages is that it is written in layman language thereby decreasing the knowledge barrier between provider and client but this also has led to self-diagnosing. Diagnoses then can become internalized and affect an individual’s self-identity, in a way reinforcing a disorder. Furthermore, under its veneer of scientific methodology it is increasingly a political instrument guiding the delivery of services and their development. Zur and Nordmarken have summarized the concerns (Zur):

. Diagnosis of mental illness remains more of an art than science due to poor clinician reliability even with the DSM. Diagnoses wax and wane in popularity according to availability of pharmacotherapy and expertsŌĆÖ influence.

. The DSM gives the false impression of supporting a bio-psychosocial and cultural model for mental illness. Although there are five axes for diagnosis, including one for psychosocial stressors, these are rarely used. It supports primarily a biological model of mental illness.

. The DSM tends to pathologize normal behaviors rather then emphasizing, a fully dimensional, spectrum, or functional impairment approach.

. American psychiatrists, insurance companies and the psychopharmacological industry control the DSM. It has become a lucrative business for them.

ŌĆ£In increasing the generality of the already large group of (dispositifs) devices described by Foucault, I call device all that has in one way or the other the capacity to capture, orientate, determine, intercept, model, control and insure the actions, conduct, opinions and discourse of living beings.ŌĆØ — Giorgio Agamben

For me, this body of work is not anti-DSM, anti-psychiatry, anti-diagnosis or anti-pharmacotherapy. It is not against books per se as instruments for the dissemination and control of knowledge.┬Ā But it is against the unquestioned and unbalanced use of any mode of intervention by health care providers and uninformed acceptance of those interventions by their clients. It is against any theories or treatment approaches that diminish the importance of the unquantifiable humanness necessary in health care. It is against providing health care as a for-profit business.

This work is about questioning ŌĆ£power relations in a given society, their historical formation, their source of strength and their fragility, the conditions that are necessary to transform some and abolish othersŌĆØ (Foucault). It is about recognizing text as a continuously changing construction with personal, cultural, political and spiritual associations.

To explore a subject I like to use a variety of strategies to gain a better understanding. This often involves drawing on our visual, tactile, auditory and–when appropriate–gustatory senses. I also like to have viewer participation when possible. This is to stimulate a dialogue and self-reflexion.

For my first carved DSM I sought a physical connection by carving it laboriously out with a hospital spoon that I manually filed and sharpened. It took a week to get through it. I then chewed some of the carved out paper and recast it into book size blocks with cornstarch and sugar (the binding components in pills). I captured the sound of the scratching and filing to play softly in the office where it was installed. My concerns about the ephemeral and tenuous nature of these and related texts led me to carve landscapes in them. I did so with chisels treating the books as informed blocks of wood (codex in Latin) that signify a way of thinking about mental disorders and their treatment. Throughout the carving process I documented profusely with photography and with sound, like an archeological dig and with the goal of creating a time-lapse video. DSM I was captured in amber (Resin) like a fossil.┬Ā I sculpted open pit gold mines from around the world as man made landscapes and continued to make objects with the carved out paper by paper casting into plaster molds I made. Some of the book altering strategies have similarities with the works of Samaras, Latham, Dettmer and Laram├®e cited above, although they are more specifically connected to the contents of these books.

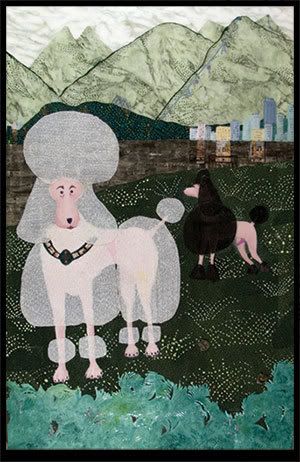

To emphasize the insidious dependence training manuals create on practionners, I thought of guide dogs for the blind and put together DSM Training guide dogs. The guide dogs invite viewer participation as they are on wheels so they can be lead around. Since it was not desirable to ask people to taste, or chew and spit these books, I decided to install the diagnoses in Fortune Cookies, playing on the criticism that the diagnostic process is unreliable.

This project draws me back to my 2007 artist statement. It is interdisciplinary in its nature and by the issues it addresses. It allows me to express my concerns on an aspect of mental health care in a visually aesthetic and metaphorically manner. Hopefully, it will also be art that helps in the understanding of these concerns. Being invited to install it in a psychiatric hospital in an emptied wing adds further personal satisfaction and meaning.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. ŌĆ£Giorgio Agamben. What is a Dispositive?ŌĆØ 2005 European Graduate School. Oct. 26, 2010.┬Ā http://www.egs.edu/faculty/giorgio-agamben/videos/what-is-a-dispositive/

Bright, Betty. No Longer Innocent-Book Art in America, 1960-1980. New York NY: Granary┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā Books, 2005.

Drucker, Johanna. The Century of ArtistŌĆÖs Books. New York, NY: Granary Books, 1995.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Sept 06, 2010 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diagnostic_and_Statistical_Manual_of_Mental_Disorders

Hubert, Riese. Readable; Visible: Reflections on the Illustrated Book, Visible language 19,4: 521, 1985.

Landow, George. ŌĆ£Hors Livre.ŌĆØ Modern Painters. Nov. 2008 p. 71-77.

Laram├®e, Guy. ŌĆ£Les Aventuriers du Mythe Perdu, LŌĆÖespace travers├®.ŌĆØ Reflexions on Interdisciplinary Practices in Art. Trois Rivi├®res, QC:┬Ā Editions DŌĆÖArt Le Sabord, x 2000, pg. 160-179.

Shapiro, David. ŌĆ£A View of Kassel.ŌĆØ Art Forum 16, 1:62, 1977.

Upchurch, Michael.┬Ā ŌĆ£The Book Borrowers: Contemporary Artists Transforming the Book.ŌĆØ┬Ā At BAM. Originally published Fri., Feb. 27, 2009; viewed Sept. 9, 2010. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/thearts/2008790462_bam27.html

Zucker, David. “Psychiatric manual’s update needs openness, not secrecy, critics say”.┬Ā Originally published December 27, 2008; viewed Sept 12, 2010. http://www.chicagotribune.com/features/lifestyle/health/chi-dsm-controversy-26-dec27,0,3080538.story.

Zur, O. and Nordmarken, N. ŌĆ£DSM: Diagnosing for Money and Power.” Summary of the Critique of the DSM. Sept. 6, 2010 http://www.zurinstitute.com/dsmcritique.html.

List of Works

Altered Books

Manuel Diagnostique et Statistique des Troubles Mentaux Texte R├®vis├® (DSM IV) Gratt├®,┬Ā 170 x 240 x 40 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III)┬Ā Gutted .

190 x 260 x 45 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV)┬Ā Chained,

Book and metal chains, 185 x 260 x 50 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III), Canyonized, 190 x 260 x 45 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III) Badlands,

190 x 260 x 45 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III) Ceci nŌĆÖest pasŌĆ”, 190 x 260 x 45 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) Quick Reference Guide, Quick fix, book and metal hinges and handle with pill like candies, 107 x165 x 20 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM I) discovered, book in resin with cigarette buts, 280 x 280 x 30 mm, 2010

DSM Case book, cases, 150 x 230 x 23 mm, 2010

DSM Cas Critiques, Glac├® (Frozen), book in ice on metal stand, 160 x 240 x 20 mm, 2010

6 Compendiums of Pharmaceutical SpecialtiesŌĆōThe Canadian Drug Reference for Health Professionals (CPS) open pit gold and diamond mines:

Argyle mine-Australia, 240 x 290 x 60 mm, 2010

Castle Mountain mine -United States, 240 x 290 x 60 mm, 2010

Illegal open pit mine- Congo (2 CPS), 240 x 290 x 120 mm, 2010

Timmins mine- Canada, 240 x 290 x 60 mm, 2010

Udachnaya mine-Russia, 240 x 290 x 60 mm, 2010

6 DSM Training Manual dogs, toy stuffed dogs on wheels with leashes, variable sizes from

400 x 400 x 300 mm to 330 x 230 x 200 mm, 2010

Synopsis of PsychiatryŌĆōBehavioral Sciences, Dog-eared, 190 x 265 x 33 mm, 2010

DSM Internet Companion, book and manual typewriter, 280 x 280 x 30 mm, 2010

Paper Castings

PavlovŌĆÖs Bell, paper cast from Synopsis of PsychiatryŌĆōBehavioral Sciences, Dog-eared, 170 x 330 mm, 2010

Ceci nŌĆÖest pas ŌĆ” ,Paper cast from The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III) Ceci nŌĆÖest pasŌĆ”150 x 120 x 30 mm, 2010

Segnosaur eggsŌĆō Cretaceous period, Paper cast from The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III) Badlands, 230 x 170 x 60, 2010

5 DSM and CPS mirrors, paper cast from CPS and DSM books, variable sizes from 600 mm in diameter to 220 X 32 mm, 2010

Ice pick, paper cast made from Synopsis of PsychiatryŌĆōBehavioral Sciences, Dog-eared, 300 x 50 mm, 2010

8 DSM and CPS Angels, paper cast from CPS and DSM books, 90 x 60 mm, 2010

Manuel Diagnostique et Statistique des Troubles Mentaux Texte R├® R├®vis├® reconstitue, paper, cornstarch, sucrose, saliva, 130 x 180 x 20 mm, 2010

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM III) reconstituted, paper, cornstarch, sucrose, saliva, 130 x 180 x 20 mm, 2010

Edibles

400 DSM Fortune Cookies individually wrapped

Photographs and Video

The DSM Re- Revised Book , 25 digital prints, 8×10.5 in. on archival paper bound in 310 x 330 x 30 mm., 2010

12 DSM and CPS excavation series digital prints 12×16 in.

Video and sound

DSM and CPS excavations time lapse video ŌĆō40 minutes

In 2004, I completed a series of 4 paintings regarding my view on the medical professionģ my profession. I portrayed the businessman doc, the one who accepts gifts from the drug companies and still believes he is not influenced. I portrayed the patriarchal doc who tells his patients how to live, as if he knew the right way, and finally the western scientific doc for whom there is always a cause (usually biological) to explain our woes. The 4th painting is more self-referential. In my silhouette is the following text:

In 2004, I completed a series of 4 paintings regarding my view on the medical professionģ my profession. I portrayed the businessman doc, the one who accepts gifts from the drug companies and still believes he is not influenced. I portrayed the patriarchal doc who tells his patients how to live, as if he knew the right way, and finally the western scientific doc for whom there is always a cause (usually biological) to explain our woes. The 4th painting is more self-referential. In my silhouette is the following text: